Phoenix, Fall 1959 “Who makes the bridal bed,

Birdie, say truly?”-

“The grey headed Sexton

That delves the grave duly.”

Sir Walter Scott

IT WAS NINE O’CLOCK on a sparkling Saturday morning in October. The squirrels had apparently retired for a mid-morning siesta, and Wes arose stiffly from his position beneath a towering shagbark hickory. An orange sun was climbing the eastern sky rapidly and drenching the dripping woods with an unseasonable warmth. Wes leaned his rifle against the tree and unbuttoned his jacket. He felt a little irked at having missed the squirrel. He had seen four or five, but that had been his only good shot-the one that came slithering down the tree directly in front of him. At the shot, the squirrel had jumped from the side of the tree and for a minute Wes thought that it was hit. Then he heard the squirrel scamper off among the dead leaves.

Wes picked up his rifle and started slowly for home. He still had the yard to mow. A well worn path led through the cool shade of second growth hardwoods-oaks and hickories. The damp leafcarpeted woodland floor was punctured haphazardly with moss-padded grey limestone. The path led past the remnants of an abandoned quarry. Wes paused to chunk a rock into the green algae covered water of the quarry hole. Then he turned off onto the railroad track. It was longer home this way and harder walking among the rotting ties and lecherous honeysuckle. The sagging rails were brown and rusty with disuse. Wes walked along them, placing one foot carefully in front of the other, falling off every few steps. He followed the path of the old railbed until it turned east across brown harvested fields. Then he turned into the woods again.

In a rain-washed red clay gulley he stooped and picked up a flattened hog-rifle ball. He scraped the mud from the oxidized lead and examined it. Well. Wes wondered when it had been fired, who had fired it, and at what, or whom? Perhaps some early settler or explorer had aimed it at a menacing Indian. More likely it had been intended for game for a table of some later date, when the Indians were all gone. Perhaps it had been fired only thirty or forty years ago. The old muzzle-loaders were used in this part of the country until fairly recently, he knew.

As Wes examined the rifle-ball, the woods became populated with ghosts of lean, rangy frontiersmen with powder-horns and bullet pouches slung from their shoulders and carrying long-barreled, brass-trimmed rifles with brown and gold maple stocks.

Wes pocketed the relic and walked quietly through time-haunted woods.

It was probably the discovery of the rifle-ball that prompted him to look for the burial plot. He had been there once before with the Ford boy and though that he could find it again.

He increased his pace until he came to the road. Crossing to the other side, he climbed through a disreputable looking barbed-wire fence, and struct out in the direction of the burial ground. The trees were strung with glistening dew-beaded spider webs, which Wes occasionally ran into, and the sun was getting a little warm for his heavy clothing.

The cemetery was not exactly where he remembered it being, and he stumbled upon it almost by accident. As he entered this forgotten resting place, the rich and lonely haunted feeling thickened in the air.

Here in the graveyard, scrubby pines grew boldly within a circle of oaks and hickories. The stones nestled secretively beneath the tangled honeysuckle. They were moss-mellowed and weather-stained in that rustic way which charms lovers of old things.

Wes moved about among the stones pushing back the choking vines and weeds and reading the inscriptions. So old they were. So forgotten; especially forgotten. Just a few feet beneath this soil lay the chalky bones of people who had, in all probability, walked here even as he did now. The bearded stones themselves seemed arrested in that transitory state of decay which still recalls the familiar, which pauses in the descent into antiquities unrecognizable and barely guessable as to origin.

1834, for instance, was a year one could remember. In this year, a stone said, the Source of Life has reclaimed His own-one Susan Ledbetter. Susan had lived on this earth a full seventeen years.

From a simple carved stone, the marble turned to a monument; from a gravestone, to the surviving integral tie to a once warm-blooded, live person. Wes pictured Susan:

She was blue-eyed and yellow-haired, soft and bright in her homespun dress. (1834 was a year one could remember; not like 1215 of 1066, but a real year.) Susan sat at the table with her parents and brothers and eyed with pardonable pride the meal she and her mother had prepared.

There were stacks of steaming golden cornbread eager to soak up the fresh churned butter. A bowl of collard greens and one of pinto beans, each laced delicately with the flavor of pork scraps. And the fragrant platter of fried pork tenderloin. Stewed apples crowded in a chipped blue chinaware bowl, and an earthen crock of cool buttermilk promised respite from the heat of the day. As Susan watched her brothers eat she swelled with womanly pride.

Susan should have a lover, and the lover looked strangely like Wes. He came courting, a gangling 18 year old, with dark serious eyes and a quick grin.

On warm summer evenings they sat on the front stoop and talked about the things they knew: neighbors and folks and crops and childhood and parents. The boy tried to tell her funny things he had heard the men say at Josh Moore’s store, but they never had the same ring to them. She laughed, or smiled, but he felt an empty flatness in their repetition. And so he told her the things he dreamed of, bashfully at first, but always dark eyed and serious. He spoke softly and slowly, looking up from the ground occasionally to glance at her, or inadvertently stop her heart with his quick grin.

They discussed death and bass-fishing and square dances, and the epic of life around them seemed to unfold. They imparted to each other a great deal of understanding.

And so they fell in love; he first with her eyes and hands and then her shoulders and soft rounded hips; she with his arms and neck and wild brown hair.

Not that they spoke of these things. No words of love passed between them, and at night when he kissed her standing there on the stoop and wheeled around and headed for the gate, it seemed that he must tell her how he felt. He would turn at the gate and look back and see her standing luminescent beneath the autumn stars and he wanted to run back and crush her in his arms and whisper wild things in her ear. But he simply raised his hand and she hers, and he ambled home emptily beneath wind-tortured trees that spoke in behalf of the silent stars.

You walk here, as so many others have walked. The ancient oaks have seen them. The lifesap courses through these twisted limbs as it flows hot through your veins- for awhile. The branching creek-rooted cottonwood cares not for the trees that sucked at this damp earth before its birth, but only for the earth, and the sunwarmth, and the seed. You walk here. Moonwarmed and wind-kissed, you walk here… for awhile.

And the boy ambled home and eased wearily into bed and tossed and rolled so that the bed-ropes had to be tightened for the second time in two weeks.

In October the first frost glazed this remote valley. The harvesting was done and preparations were being made for Winter. Great stores of food were being laid away in earthy cellars and musty smoke-houses. The rich smell of wood smoke hung in the valley, promising the peace and warmth of winter nights before a friendly fire. The savory aroma of hog-meat being cooked in great black outdoor kettles spoke of bountiful tables and festivity within the house-warmth of winter. It was a very good time of year. The time of year when one reflects with satisfaction on a well done summer’s work.

For Susan it was a very good time of year. She kept busy with endless household chores and minded them not in the least. In fact, she was barely conscious of them and more than once was surprised, upon turning to some project or other, to discover that she had already done it.

Had she been superstitious, she might have insisted that some kind fairy folk had washed the tomatoes that she left on the sideboard.

Perhaps her thoughts were a little too much taken with a tall lean and dark-eyed man (to her he was very much a man, and perhaps he was). As yet there had been no serious talk between them, but she knew, and she was willing to permit him to take his time. The question of her future was settled quite agreeably and her youth told her all was well. Give him time; all will be well.

The boy himself was likewise busy with chores. It was a busy time of year, a good time of year. The crisp mornings got one out of bed almost by force. Fried eggs and sausage tasted so much better when there was frost in the air. As he swung out the door swinging the milk pail the tingling air filled his nostrils with seductive promises.

Chickens scattered at his approach, clucking nervously. He swung his pail at them and laughed as they broke into panic. Passing the wood ricks he noted with satisfaction that nearly all the logs had been cut and stacked in martial order between poles and driven into the ground. There was a full cord of shiny triangular sticks of split yellow pine kindling. The very air seemed glutinous with rich plenty. Reaching the barn (it was a small shed of great weathered planking), he loosened the leather thong from the nail and entered with a loud and hearty greeting for the surprised milch cow.

Diurnal forces carpeted the forest floor with thick layers of crunchy brown leaves, torn from the halfnaked trees. Long enough these leaves had shaded the wooded ridges and slopes. Now they returned to the earth to decay and so provide life and sustenance for their unformed successors. Long enough, leaves.

The year was 1834, and a very fine year it was. It was fall, and that is a good time of year.

In a rocky woodland glen, a minor tragedy occurred. A fox, a little lean (even foxes walk noisily in crisp leaves), had managed to cut off a very frightened striped chipmunk from his home among the piled stones. The fox sprang full upon the chipmunk, but before he could get his sharp little teeth into the furry prize, it had slipped between his legs. The fox whirled frantically and pounced again, this time pinning the chipmunk between his forepaws. Cautiously he lowered his head to complete the capture. He opened his mouth and released the pressure of his paws, but the chipmunk was too quick for him. His teeth clicked with a clear ringing snap in the frosty air.

The chipmunk was a flash of golden brown streaking for a crevice in the rocks. Just as it gained this refuge, the fox, by a combination of agility and luck, pinned it down with one paw. But the chipmunk was inside the crevice and the fox could not get his sharp pointed snout through the crack far enough to reach it. Furthermore the chipmunk was worming forward even under the pressure of the fox’s paw, until it was wedged down into the rocks where the fox could not dig it out. The fox thrust his face into the crevice as far as it would go, which left the warm fragrance of the chipmunk several inches in front of his nose, and whined like a puppy. He scraped and clawed at the chipmunk until it was bloody and lifeless, snuffed loudly, and with one last despairing whine trotted off through the noisy leaves, leaving the chipmunk for the smaller carnivores.

The weather had grown too cold for out of door sparkling. (It was October and the valley shone with white glistening frost beneath the long slanted rays of the rising sun.) It was good hunting weather and the woods echoed periodically with the sharp crack of rifles or the deeper hollow sound of the fowling piece. But the weather had grown too cold for out of door sparkling. Susan and the boy occasionally sat in the front room of her house on chilly evenings and shared conversation with her parents and her brothers. The brothers were tolerant, but a little amused, and they made the boy uncomfortable.

Sometimes everyone would go to bed and leave the two of them alone for a little while before the boy had to depart. On these occasions the boy was even more flustered than when the family was in the room.

He would say, “Well Susan, I guess I’d better be getting along.” And she would say, “o don’t go just yet, it’s not so late.” And he would say, “Well, I’ll have to be leaving pretty soon,” and look darkly at her until she lowered her head with an embarrassed smile and then he would reach over a little awkwardly and kiss her on the cheek. She would look up, just a little, and he would hold her shoulders and kiss her on the mouth. Nothing was ever so soft and warm and sweet scented. He would hold her for awhile, not speaking, but his breath catching a little in his throat, distrusting his voice altogether. After awhile she would look up an him, rather boldly, he thought, and ask him would she see him tomorrow, or would he be at Arwood’s Saturday night, or what, and he would answer as best he could, kiss her on the cheek and say he’d better be going and rise stiffly and stand there stoically, or maybe even stretch, and then cross the room, feeling awkward, and get his coat.

At the door her kiss would be full of meaning and he would tumblr out into the sharp night air and run most of the way home. The stars promised they would be back again tomorrow night.

Susan would stand at the door until he was out of sight, breathing very quietly and imagining him still there with his arms around her.

Then she would carry the lamp into her room and look at herself to see what there was about her that made him think she was such a delicate piece of china.

Undressing quickly in the cold little room, she would tumble into bed. She would see him again tomorrow night.

The stars came back; if their luster paled, it was because of a part of beauty was no longer there to receive them. In his eyes they swam blurred and distorted in a salt sea. The year was 1834, and it was October.

How had she died? The mute stone left no testimony. There were so many ways.

A sea of love and pity welled up in Wes. Great tears pushed one another down his cheek. He threw his arms around the unyielding stone and wept for lost Susan, for all the lost Susans, for all the people; so beautiful, so pathetic, so lost and wasted and ungrieved.

Later Wes arose from the spot, drained and empty. He picked up his rifle and started for home. Winds were about. A little band of dead leaves jumped beneath his feet and frolicked and tumbled ahead of him, then did a disorderly right oblique and scampered crazily down a sunny woodland corridor, leaping and dancing before the wind in a travesty of life.

Wes smiled. Leaves tired and dropped sighing from branches.

Long enough, leaves.

He smiled, and walked home, towering even among the lean trees.

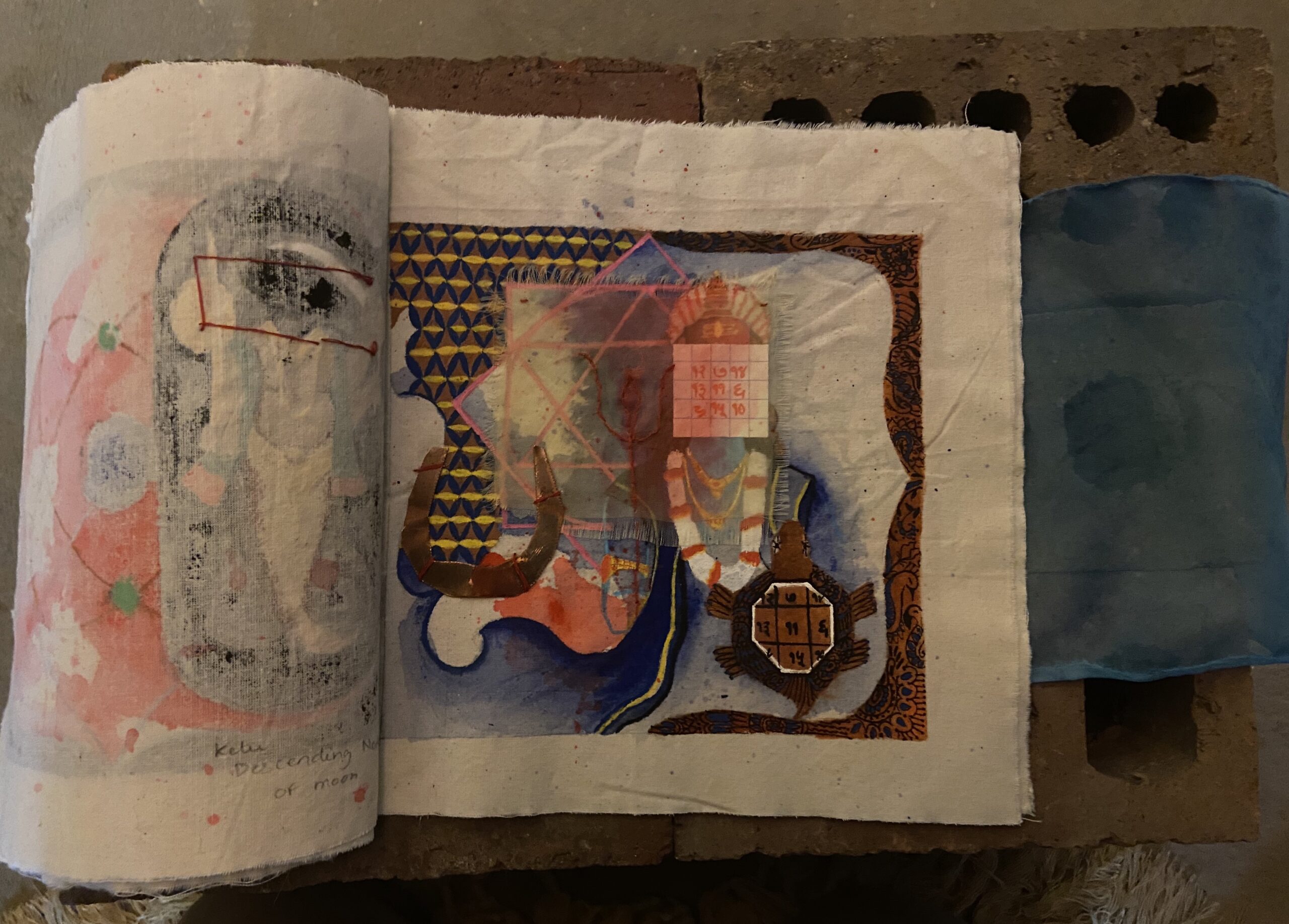

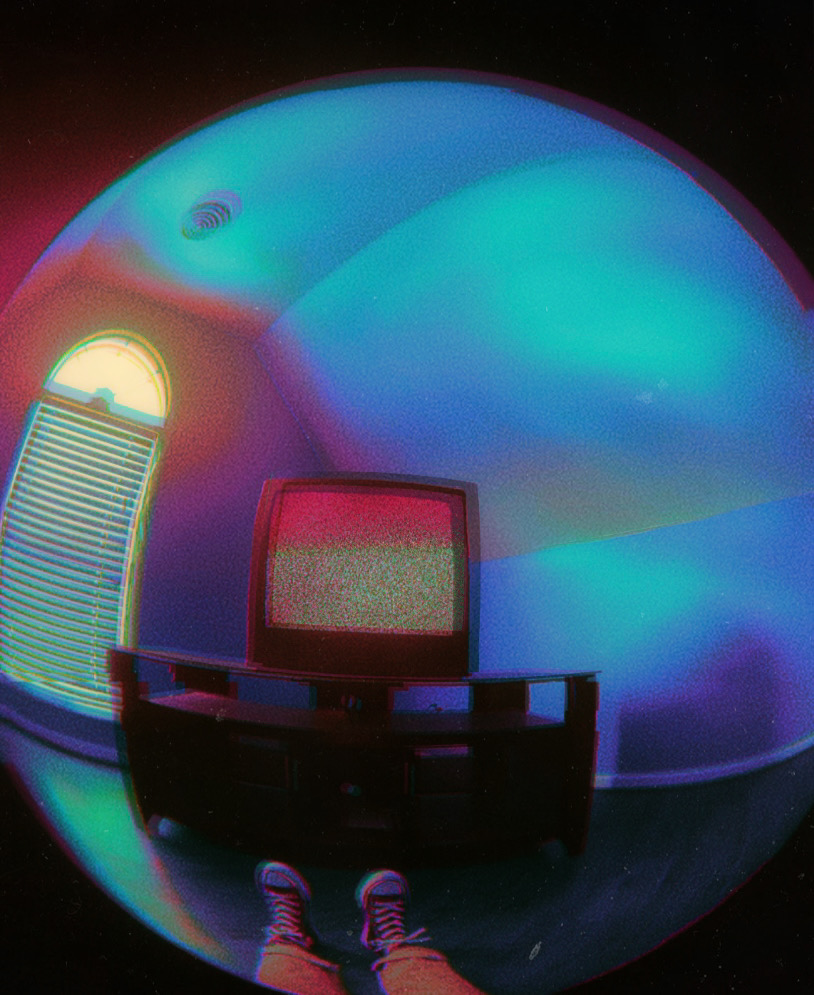

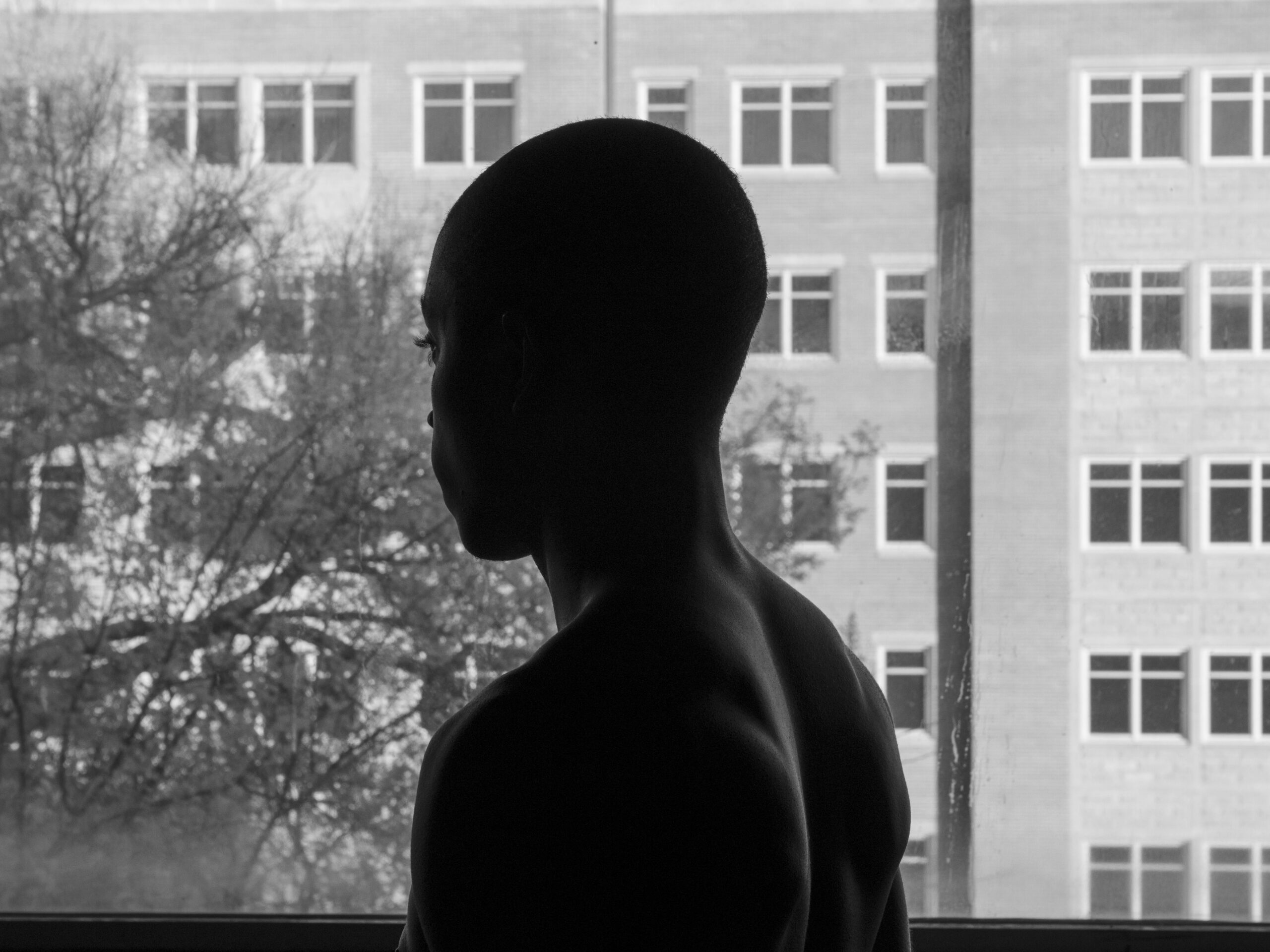

Artwork: “Antithesis to Lomography” by Diana Dalton

Written by Diana Dalton

Written by Diana Dalton

Written by Aslan Gossett

Written by Aslan Gossett

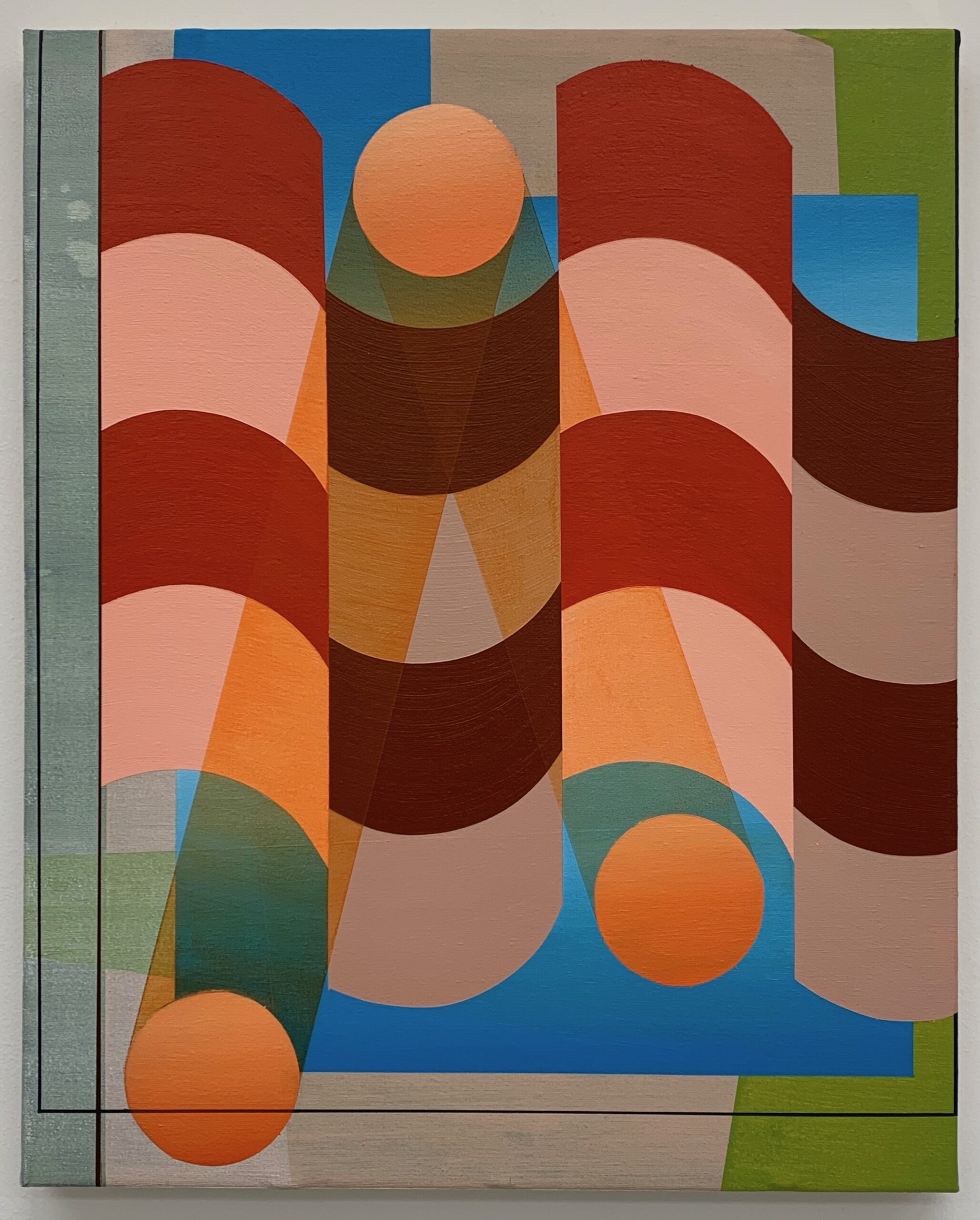

Taylor Kolnick

Taylor Kolnick

Natalia Mahan

Natalia Mahan

Lauren Farkas

Lauren Farkas

Megan Wolfkill

Megan Wolfkill

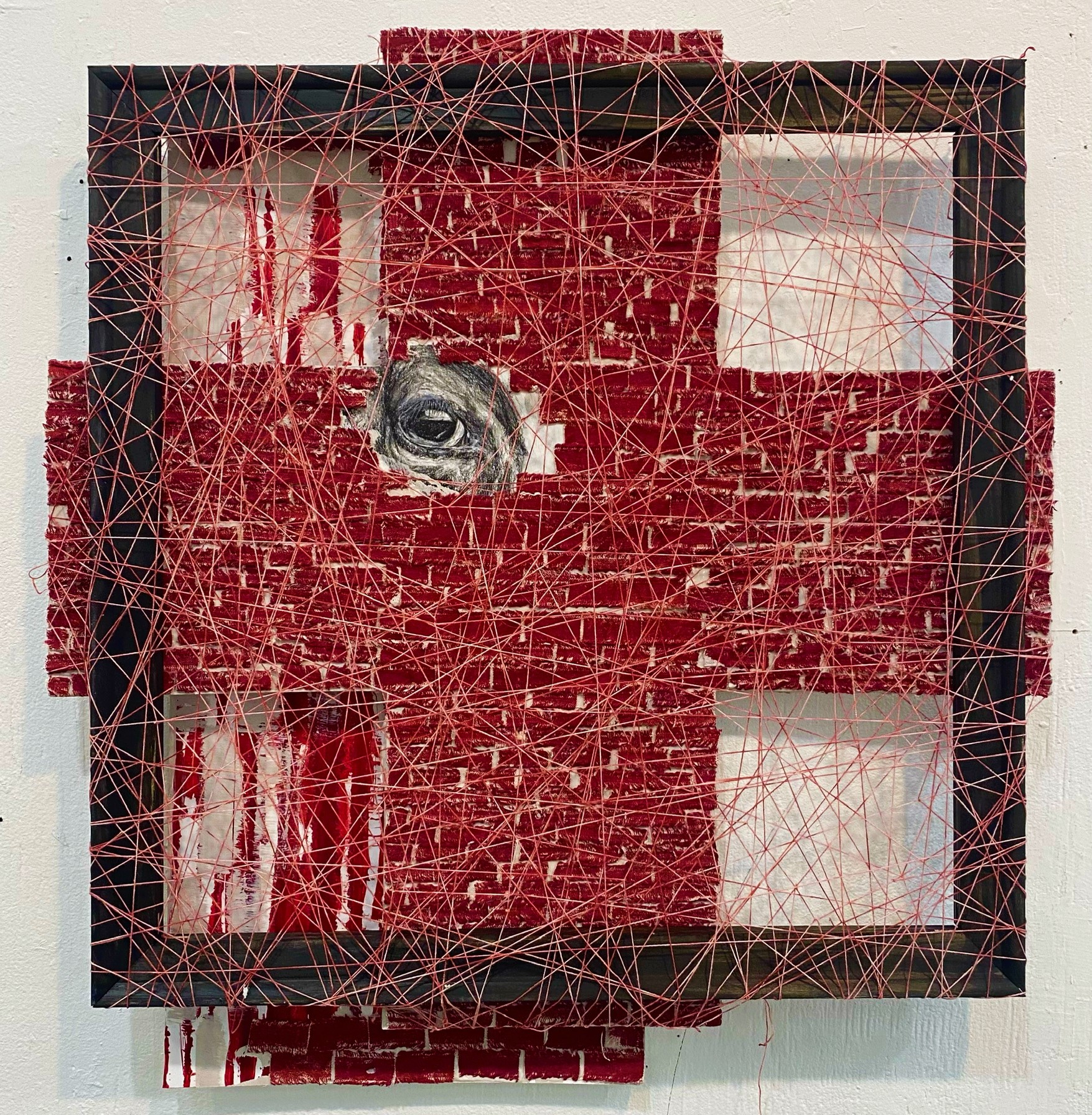

Jana Ghewazi

Jana Ghewazi

Rae Taylor

Rae Taylor

Jackson Jalomo

Jackson Jalomo Adarian Johnson

Adarian Johnson

Diana Dalton

Diana Dalton

Written by Sadie Kimbrough

Written by Sadie Kimbrough