Faith Belt is a senior art student at UTK working in drawing, ceramics, and puppetry. Her creative process is driven by the concepts of seeking, reaching, and wrestling. Belt’s infatuation with storytelling leads her to incorporate the tales of Gilgamesh, the Swan of Tuonela, and various mythologies into her work. Her clay sculptures, sketches, and puppetry portray layered narratives that continue generational archetypes and the art of storytelling.

Phoenix Magazine

A Journal from the English Department at the University of Tennessee

-

-

Written by Clint Liles

Written by Clint Liles

Edited by Sadie KimbroughHaley Takahashi, an award-winning artist and graduate student here at the University of Tennessee offers representation of being a Japanese American and the duality that identity brings in present-day America. Her work centers around family and identity through a blend of modern printmaking techniques and traditional Japanese imagery. In doing so Takahashi creates profound and memorable works of art that leave the audience grappling with her message.

Takahashi told me that art has always been present in her life, even as a little girl.

“I have always done art. My dad was an art teacher and it was always a part of my life from the very beginning. I’ve never not done some sort of art at some point in my life.”

However, she highlights that becoming an artist was not her original plan.

“There have been multiple levels of ‘this is just a hobby’ or ‘this is an actual thing I want to pursue.’ In my undergrad I went in as an Art History major because I had a lot of people and society in general telling me that getting an art degree wasn’t worth anything. I was so scared that I was just like, ‘Okay, if I want to do anything, I want to do something art,’ so I majored in Art History.”

In many ways, her decision to pursue art further was a journey aided by supportive professors and friends who challenged her.

“As an art history student, I was only allowed to take a very small amount of art classes. At the time I was a studio art minor and went in, had a fantastic time and the professor approached me and said, ‘Why are you an art history major? You’re an artist, obviously you have always been an artist.’ I was like, ‘You’re right, what’s the point in trying to hide it?’ That was a good ‘aha’ moment when I allowed myself to say, ‘Okay I’m going to do art, I’m going to continue art, I’m going to go into grad school for art.’”

Takahashi notes that self-identity plays a major role in her work.

“I’m Japanese American and half white. I have this really interesting socialization and existence within American society. I think creating something speaking back to that is really important.”

Takahashi also opened up to me about how her family history plays a major role in her work as well.

“I’ve spent a lot of time researching and focusing on my dad’s side, which is my Japanese side, because there’s a lot of trauma to unpack within that. So, there’s Japanese internment and then not being white in America and what does that look like? What does that mean? So, when I do work about it, it’s kind of me working through those emotions and doing research through that end of it. And as of late I’ve been thinking more about how to contextualize my upbringing being biracial because it’s very subjective. Not every person who had one Asian parent and one white parent has the same upbringing. So, how can my family and my history inform my work?”

She also notes that red is a common motif that she finds throughout several of her works.

“At first these motifs were a little subconscious, but as I’ve thought about it a little bit more the red gradient for me can mean so many things. Red is passionate, angry, and bright, the idea of it fading into nothing is metaphorical and poetic. Red is so culturally Japanese and that’s something I’m always grappling with; my identity as a Japanese American.”

A piece that really stuck out to me was her work, “This Land is Soaked in Blood.” Haley offered more background on this piece and her intentions behind the work.

“I put it on this big kimono that sweeps the floor and has that red gradient that’s almost soaking up this anger. I was thinking about how if we don’t teach history and we don’t learn about it deeper than what we are taught in schools, then it’s bound to repeat itself.”

A message could be seen even while she worked on the piece.

“I made that right at the time when the government had placed a ban on Muslim people travelling or immigrating to the US and when people are being detained at the border. And it was just like, how can I hit the audience with the face of the history that this is nothing new? I’m still fighting to get that same energy back into my work now.”

For several reasons this piece also held personal resonance with her as she noted of her own family history in relation to it.

“My family on my dad’s side was sent to internment camps in the 1940’s and so much of my family’s culture was just taken away. It was not okay to be different or Japanese, you had to conform and I resent that. I’ve put a lot of anger towards that, that I never got to learn Japanese, we don’t have our samurai armor, my family had to sell their house and all these very salty and angry feelings. So, I printed that fabric with the executive order that Japanese people were going to be taken from their homes and taken to these camps.”

Takahashi shared with me that she’s still creating and experimenting with new things.

“I have been experimenting with pop-ups and pop-up books, so that’s a really exciting forefront that’s playing the line between print and 2D but also 3D. I really want to get into installation like lantern building and kimono making.”

Takahashi’s work is an acute statement to her Japanese American identity and the value of her family’s legacy. In doing so, her work creates a powerful blend of contemporary and traditional techniques that offers stunning pieces for her audience.

-

LITERATURE

White Noise by Don DeLillo (1985)

Satirical, funny, and all too real glance at American consumerism, ignorance, and the relation between self-obsession and self-deception. – Aslan A Gentleman in Moscow by Amor Towles (2016)

Super comforting read after a rough year. – Clint M Archives: After the End of the World by Alexis Pauline Gumbs (2018)

Gumbs scouts her consciousness to harbor a world reeling from environmental collapse. Everyone should read this. – Sadie

Neuromancer by William Gibson (1984)

If you were ever curious about what book pioneered the cyberpunk genre with horrifying cybernetic body modifications and incestuous tech dynasties, give Neuromancer a read! – Josh No Longer Human by Osamu Dazai (1948)

While this book is incredibly sad, I thought that it was such an interesting look at how modernism and postmodernism were implemented in the literary world of Japan. – Case The Myth of Sisyphus by Albert Camus (1942)

Essays on Absurdist existentialism and thoughts on what it means to live meaningfully without committing oneself to a set of theology, philosophy, or doctrine. – Aslan Parable of the Talents by Octavia Butler (1998)

It’s a hard read but so worth it and eerily relevant to modern times even though she wrote it in the 90s. – Clint Haruki Murakami

I made it a point to read a lot of Murakami this year for no reason in particular, but I am very glad I did! Every book that I have read by him has been so worth reading and all for different reasons! – Case

POETRY

Danez Smith, “Don’t Call Us Dead: Poems” (2017)

Cannot be summarized, must be read. – Aslan Marie Howe, “Magdalene: Poems” (2020)

Once again treats us with Howe’s blend of conventional and unconventional styles and forms on a wide birth of topics, from isolation to lies to womanhood. – AslanMUSIC

SINNER GET READY by Lingua Ignota (2021)

Powerful, angry, Appalachian, and deliciously blasphemous. – Aslan Jubilee by Japanese Breakfast (2021)

The soundtrack for every season. I won’t shut up about this! – SadieI think what made this album amazing to me is that every song on it is good on its own, but the album as a whole conceptually is also perfect. I also had the added benefit of watching her play this whole album live, and she did not disappoint! – Case

Black Country, New Road

This is my favorite artist for this year because they have consistently put out some of the best and most creative music of 2021! They blend Slint-like post-punk, jazz, klezmer, and Arcade Fire style indie rock into these entrancingly beautiful songs! – Case A Very Lonely Solstice by Fleet Foxes (2021)

Hauntingly lonely yet meltingly warm acoustics performed live. – Aslan “Crystal” by Stevie Nicks

The perfect car ride theme song. “Crystal” has been played numerous times on my Apple Music. I also recommend watching the movie Practical Magic (1998) where “Crystal” is featured. – Abby-Noelle Microphones in 2020 by The Microphones (2020)

Phil Elverum does it again. – Aslan Harry Styles by Harry Styles (2017)

This album is raw and emotional. “Two Ghosts”, “Sweet Creature”, and “Sign of the Times” are among my favorites. – Abby-Noelle Romantic Images by Molly Burch (2021)

This appropriately titled record is confident and crushworthy. – SadieFILM

The French Dispatch (2021) dir. Wes Anderson

Beautiful love letter to print media like no other. – Aslan

Yomjimbo (1961) dir. Akira Kurosawa

A delightfully masculine movie about a devil-may-care ronin (Toshirô Mifune) and his quest to rid an impoverished town of its two warring gangs. – Josh The Eyes of My Mother (2016) dir. Nicholas Pesce

Strong stomach and patience required. – Aslan

Summer of Soul (…or, When the Revolution Could Not Be Televised) (2021) dir. Ahmir-Khalib Thompson

Five minutes in, Stevie Wonder shows up. – Sadie Killing Them Softly (2021) dir. Andrew Dominik

Strange but enthralling mediation on politics and the small human’s place in the world of markets. – Aslan The Green Knight (2021) dir. David Lowery

I thought this movie was such a wonderful take on the chivalric romance! The way it’s shot like a horror movie as well as the obfuscatory ending added to the delight of seeing it! – Case Sound of Metal (2019) dir. Darius Marder

Unbelievable performance by Riz Ahmed on repressed trauma and cyclical addiction, as well as a fresh approach to (aka: lack thereof) sound design. – Aslan Spencer (2021) dir. Pablo Larraín

Kristen Stewart gives her all in this justifiably hyped thriller. Now I need a psychological biopic on one of the royal corgis. – SadieTELEVISION

Sex Education (2019)

Premiering in 2019, this Netflix TV show is near and dear to my heart. Sex Education inclusively portrays the complexity of sexuality, women’s rights, and relationships. Also, Ezra Furman does an amazing job creating a soundtrack for this show. – Abby-Noelle -

By Jenny Darden

By Jenny Darden

Phoenix: Spring 2001

TW: Allusions to Suicide1. The Disillusionment

Romeo and Juliet are dead, and this time they’re not faking.

Their dirty, naked bodies are lying beneath the apple tree, cradled in its roots, God-shamed. And we all stand around taking pictures, like they taught us to. I finally get to try out my new zoom lens. Roots ever growing downward seek hollow spaces in dirt.

Yesterday, tired and filthy and bra-less, I jumped a plane to L.A. Wanted to leave you behind, but took you with me—an unfinished scar, a poem in my head (maybe a riddle). I guess I’m just buying time: Knoxville time, L.A. time, your time, my time—it helps to know whose time we’re wasting, I think. Dying, they drew their lives in the dirt, mocking a self-portrait. We laughed and called them fools, and crunch strychnine apples until the sun came up.

2. An Epitaph for the Muses

Where she was, there’s a pair of sneakers floating in a

swimming pool.

Where she was, there’s a velvet noose and a wristwatch.

Where she was, there’s a virgin paper and unbled ink.

Where she was, dystocia killed the cow, but the cat’s

still kicking.

Where she was, rain collects, reeking, stagnant.

Where she was, endless endings.

Where she was, I bleed but can’t find a scratch.

Where she was, noise art, a dissonance experiment.

Where she was, he sits on the porch scissoring my face from

every shared pose, convinced that it only hurts because it is supposed to.

3. Flying

Having the window seat means a lot to some people. Just like having the last word means a lot to other people, and having children means a lot to still other people. I am sad that nothing means a lot to me, and sadder still that I have so nearly perfected the art of lying to myself.

4. Eden by Moonlight

Last night I dreamt that I was a statue in Eden, lovely and cold, with a round stone belly and smooth stone arms, and ivy curled between my toes. I stood barefoot and talkless in the raw pale of moonlight and watched the serpent offer Eve the apple. My helplessness immortalized, made beautiful by Him.

I dreamt a lacey mist, and I dreamt until waking, numbed and new, to turbulence and the stainless-steel gleam of the beverage card weaseling down an anorexic aisle. I dreamt a coffin and listened to the nails you hammered in, ping ping ping. And I let you rearrange me until I fit, and we slept that way all night, acting but not tasting, gnawing on the dropped, rotted fruit because it was all that we could reach t h e g r o u n d w a s a s h i g h a s w e c o u l d r e a c h.

The dropped fruit rotted on the ground, and the fallen ones reached up, up to take of it. And, in the waking, I dreamt a coffin and listened to the nails you drove in, ping ping ping, they keep getting deeper.

5. Shakespeare in Ribbons

Tonight I am thousands of miles over Honolulu with boy-shorn hair and the Bard in paperback; halfway to Sydney above a rolling and invisible Pacific—melted candle wax, a smothered wick in the east where dawn should be glowing. I am gaining altitude and gaining hours of night. I’m thousands of miles over you and rising like heat.

6. Impressions

It’s dark in the garden. In the vintage I am making apple juice, wringing knows dry as bone, leaving the impressions of my fingernails in the soured flesh. Sure that I’ve finally left him behind me, on the same porch, separating my smile from his.

Forgetting that the serpent watches through folds of trees and wisps of swaying branch; through Venetian glass eyes, soaking up impressions, swallowing moonlight with eager hinged jaws, his hunger blackening me to a shadow of myself.

Forgetting the things that I did to earn his smile.

It seems long ago.

7. Misinformation

Noah wants to be the John-Smith to my Pocahontas.

Only, it was John Rolfe who loved Pocahontas.

But I pretend with him, which may prove to be my wrongest thing I have ever done.

8. Burned

High over the Pacific, I dreamt myself at home in bed, the serpent slithering like fast-growing ivy up my bedpost and between my clean linens. With his forked tongue he seduced me, made me impure.

When it was over, I ran barefoot outside into the fields of dew-plump grass the shade of envy, shivering in the ill-fitting pink silk of “I wish I was.” Gunshots rang out, and I clutched my exploded heart and fell down into the wet grass, the sharp report still echoing in my head long after I awoke, sweating bullets and nursing dragon-singed wings, the newest member of the mile-high club.

9. Here

You’re here, and I’m calling him to tell him that it’s over.

You’re here, and wet clothes are churning in a heat cyclone,

laundromat acrobatics.

You’re here, and I’m choking on forbidden fruit swallowed whole.

You’re here, and the serpent crawling up my legs.

You’re here, and I’m here.

You’re here, the statues are crumbling to dust…crawling on

the floor after too many drinks, too many no’s…

You’re here telling me not to worry, sitting on your forked tail.

You’re here after the bars are closed, feeding me apple juice

through the tube in my arm.

You’re here, and he’s not.

10. Denouement

I woke up drunk this morning, and he thought it could be the same.

I woke up wishing that I could be hung-over.

And all the skinny white branches a-scratch-scratch-scratch-

ing at my windowpane like a cat wanting to be let in.

He talks with his hands, and stays drunk so that he will always

Have a convenient excuse, and I pretend that’s all right,

like we can just put the apple back on the tree (duct tape).

11. Disgrace

He keeps finding me poems for me, broken glass shoved up

through my foot. The statue of a murdered muse. A prelude to.

Don’t ask me what. Piano ivory beneath the weight of his fin-

gertips pressed down. And I’m getting sicker by the minute.

12. The New Crucifixion

He drives it into me, all nine inches like ping ping ping like bad

porn. He dies inside me, closed in stale like music in elevators

like music getting loud like venom dripping like honeysilk like

bobbing for apples in water music.

He softens the noose so that I’ll die longer.

13. Gotten Lucky

He left me unfinished, high above the Pacific and falling. I re-

enjoyed Faulkner on the way down, mile-high incest. I still feel

the alcohol swimming when I close my eyes. Going back to one

I never left. Should. While all the star-crossed lovers hang out

at the mausoleum nursing apple bites and making suicide. I

am the aftertaste of the processed form of the forbidden fruit. I

am a backwash apple juice in granny panties on laundry day. I

am a retro Juliet, sweet thirteen again as he tears apart my smile

and forgets the nights inside me and rising like heat music a

hundred thousand miles over; and still not over,

Still not over.

Artwork: “Parasites of the Heart” by Karen Anderson

-

Written by Clint Liles

Written by Clint Liles

Edited by Josh StrangeI grew up about two hours north of Knoxville in a small-town just south of the Kentucky-Tennessee state line. The closest city was Knoxville followed by Lexington with an equal distance drive. In many ways my experience of growing up in Appalachia was one of seclusion. I saw little representation or diversity around me in my day-to-day life. The only experience I had with seeing people in the LGBTQ+ community was confined to movies and television. Thus, those in the LGBTQ+ community felt miles away from me, living in an entirely different universe. I know that I was not the only one who experienced this form of seclusion.

To many of us who were raised or familiar with Appalachia, the idea of queer Appalachian literature feels a bit like an oxymoron. From an outsider’s view, Appalachia is a place full of bigotry and backwards beliefs. Yet, there are writers who push back against this perceived notion and write vibrant pieces on their experiences of being a part of the LGBTQ+ community in Appalachia. The collection LGBTQ: Fiction and Poetry from Appalachia is a testament to the idea that it is possible to be both queer and Appalachian, offering colorful insight into what life is like for many queer Appalachians who are proud of their mountain identity. Editors Jeff Mann and Julia Watts have worked to create a collection that is solely based on Appalachian writers in the LGBTQ+ community. As a result, they have pulled together a collection that will resonate deeply with readers who grew up queer in rural Appalachia, as I did.

These writers give a voice to the queer Appalachian experience and note the challenges, discrimination, and joy that comes with these two identities and in doing so, offer an immensely personal read. It is noted in the book’s intro that, “LGBTQ Appalachian writing nearly always concerns the ways that sexuality, gender identity, place, and family converge, interweave, and complicate one another.” This is an aspect that many of us who are queer and grew up in Appalachia can understand. The values of Appalachia- including connection to family, church, and community-are instilled within us, yet at the same time there are great challenges and a feeling of isolation for many of us in the LGBTQ+ community.

While the book speaks to several themes and issues surrounding growing up queer in Appalachia, the theme I found occurring most often throughout several of the stories is family ties to the protagonist and how this affects them in several ways. I would argue this theme is central for good reason too. Family is no doubt a fundamental aspect of life in Appalachia and Appalachian culture. Realizing that one is queer in an Appalachian family can pose challenges that several of these authors explore. They do not exclude the pain and bigotry that is so often seen in Appalachia but they also offer moments of tenderness and joy.

Jeff Mann’s poem ‘Training the Enemy’ caught my attention and held it throughout the poem. “Well Appalachia, you’ve done it./ You’ve made a man out of me.” Immediately Mann catches the reader’s attention through his economic use of language. Yet, this moment also connects with me and pulls me back to my small hometown and that desire I had to be a ‘man’ when it felt horrifying to sign up for football try-outs. It appears as though Mann had accomplished what I had tried and failed throughout much of my adolescence. Mann goes on to state, “Watch me shoot the redneck shit as well/ as any local, puffing stogies and sipping bourbon/ straight.” Mann’s language is full of contempt and a boiled-up anger that is spilling out on the page. It is this anger that offers a twist to the poem. Mann’s anger stems from that conflict of being a gay Appalachian. While he may belong in this landscape due to his presentation, not every individual within the LGBTQ+ community can comfortably say that. He’s an insider within a community that detests him. This is a rage many queer children who grew up in Appalachia feel as a result of the seemingly endless bigotry and oppression that occurs while growing up in a rural Appalachian town. This piece resonated with me personally as I grew up in an area where to be gay was viewed as an attack on masculinity, and as a result the few gay men in my hometown had to present as masculine for safety. I tried to present as masculine throughout grade-school not as a personal preference but for survival. Mann takes that same survivalist view I had to cling to throughout my adolescence and twists it into a new form of masculinity. He paints a picture that holds being gay and Appalachian in one hand, owning both identities in a way that dares against the common homophobia in Appalachia.

Overall, this collection made me feel empowered and seen as a gay Appalachian. Growing up in rural East Tennessee, there was little representation of the LGBTQ+ community offered, much less Appalachian representation of my identity. These stories feel personal to me, because in many ways they are. There were moments of flashback in the book where I shared intimate connections with the characters because of our shared experiences. It was a page turner as well as an emotional and personal experience for me as I revisited emotions I thought I had left upon moving to Knoxville. This is a book for everyone but especially those in the LGBTQ+ community.

-

Were You On the Moon

Were You On the Moon

by Brynna Williams

Phoenix: Fall 2018 You have to wake up sometime.

That’s what I’d like to say to myself,

but it’s so peaceful to sleep.

Warm hands on my back,

the moment I open my eyes,

will feather into wings, birds,

fly into the sun

and leave me freezing.

If I wake up,

I’ll have to abandon the stars

I’ve been camping between,

that tent made of crystal dust,

the sleeping bag stuffed with tears.

I can’t stay here forever,

and I know it,

but I still have to.

All this time,

I’ve been swallowing spoonfuls of you,

trying to keep that taste tucked in my cheeks,

to line the backs of my teeth,

dye my tongue your favorite shade of blue,

but it just won’t stick.

There are so few moments left,

and I can’t help but be aware

I’m the sand in the hourglass,

slipping back through to the other side,

no hands to hold on.

One more turn around the moon;

I thought I’d make it in time,

but there were footprints in that green-gray dirt,

tiny beside the craters,

with clouds hovering above them

of that very same dirt,

perfectly still,

as if they’d

just been

left.Artwork: “Random Weave” by Dana Potter and Lila Shull

-

Written by Case Pharr

Written by Case Pharr

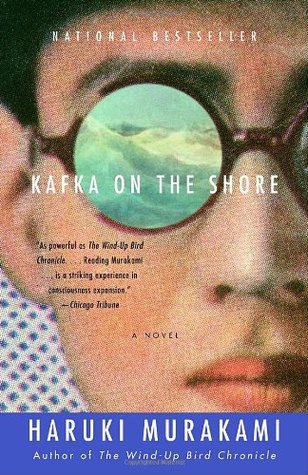

Edited by Sadie KimbroughKafka on the Shore is a magical realist novel by famed Japanese novelist Haruki Murakami. Framed in modern Japan, Murakami weaves a novel which explores metaphysics, utilizes Sophoclean prophecy, bridges dreams and reality, pits determinism and free will against each other, and most of all engages the reader on both an emotional and intellectual level.

Kafka on the Shore has a dual plot, alternating every chapter between the story of an adolescent boy as he flees the police after his father’s mysterious death and an elderly man man who lost his memory as well as his ability to read and write due to a bizarre childhood incident. The novel begins with the story of young Kafka Tamura, son of famed sculptor Koichi Tamura. Kafka has grown up with the conspicuous absence of his mother and sister, of whom he has only one picture. He flees his childhood home after his father prophesies that Kafka will kill his father and have sex with his mother and sister. In his flight, he begins living and working at a library where he makes the acquaintances of the mysterious Miss Saeki and Oshima. As he gets closer to these two, he begins having mysterious vivid dreams which eventually culminate in a journey beyond the physical realm and into a liminal space.

While Kafka is on his own odyssey, the tale of the elderly man, Nakata, is told. Beginning with a strange encounter in his elementary school years during World War II, Nakata’s whole class goes unconscious at once, but only Nakata remains unconscious for an extended period of time. When he awakens, he is unable to remember anything, and he cannot read, write, or form complex sentences. However, Nakata has a strange ability to speak with cats, and he uses this ability to look for lost pets. Eventually Nakata saves a cat from a man, by the name of Johnny Walker, who is about to kill it. He kills Johnny Walker in order to save the cat, setting into motion his own journey, which eventually results in his opening a sort of portal into another realm.

Murakami connects the two disparate plots by sending Kafka through the portal which Hoshino, Nakata’s friend, opens. This portal is both physical and metaphysical as Kafka enters a sort of world of ideal forms that both exists and does not. While the world he enters through the portal is idyllic and almost perfect he decides that he would rather live a normal life and grow old and chooses to leave.

Murakami’s novel is a masterclass in the use of the magical realist genre. Each character’s story is framed in a setting which appears mundane, however, Murakami fractures these realistic surroundings by peppering in more and more of the surreal as the novel progresses. He is able to call up such deep and universal themes with his simple prose and compelling narrative. There is something in the novel for any reader to appreciate. Whether it be the allusions to classics such as Sophocles or the charming nature of his characters, Murakami’s Kafka on the Shore is both accessible, beautiful and thought provoking. Ultimately, Kafka on the Shore is a story about the relationship between fate and the fight for free will. The prophecy set before Kafka and the spectre of the childhood accident which haunts Nakata serve as clear calls to a sort of quest which both characters undertake. It becomes increasingly uncertain whether each character is acting under his own agency or that of some higher deity like power. However, Murakami almost subverts this binary opposition between wyrd and free will as he shows how each character’s choices, while free, fundamentally align with and fall into a predetermined fate.

It is impossible to capture in such a short review the breadth and beauty captured by Murakami in these pages, however, I would encourage everyone to read this book. It is a work of art which is both compelling and complex enough to satisfy anyone reading it.

-

Written by Josh Strange

Written by Josh Strange

Edited by Sadie KimbroughIt is a societal mainstay that many, if not all, are familiar with seeing in Christian art; curly-haired, handsome men, are shown representing either Jesus himself or other biblical figures. For many, it would be impossible to imagine the religious figures of the Bible as anything other than handsome white men with hair flowing their shoulders and doe-like eyes staring sympathetically into the souls of the believers. What might not be as familiar to many is the origin of this artistic motif and its ancient, homoerotic inspirations that would become inseparable from the way that the people of the world imagine the appearance of Jesus and his disciples. As with many things in our modern society, the origins of these cultural hallmarks can be traced back to the European Renaissance.

Before the Renaissance, religious art in Europe was dominated by two-dimensional illustrations and elaborate calligraphy in large written books known as illuminated manuscripts. Realism, in this time, was not a focus in art and the obsessive attention to anatomical detail that was characteristic of Greco-Roman art had been dead for centuries. It was only until the mid-14th century, with the rediscovery of these ancient texts and artworks that the Renaissance began as an artistic movement.

The Renaissance was a time in which the Classical art of the ancient Greek and Romans reentered popular Western European culture. Many of the nobility and clergy of Europe were amazed at the sophistication and majesty of these art pieces. Naturally, they then sought to emulate the grandeur that they saw before them, so they commissioned the best artists in Europe to take inspiration from the ancient pieces. Gradually, recognizable techniques and motifs of the Ancients began to make appearances in Italian art in the mid-14th century.

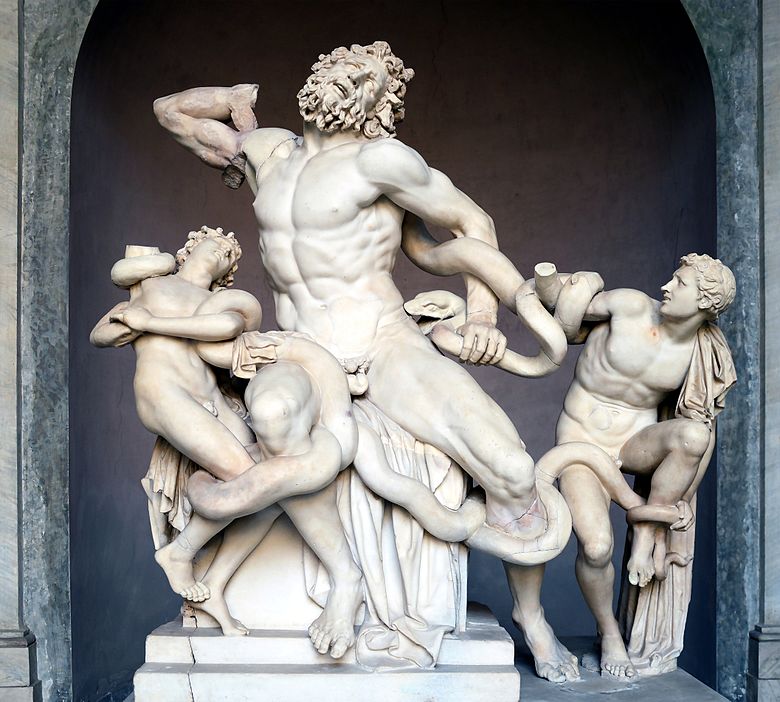

Prized more than any other form among the ancient Greeks and Romans was the nude male body. Magnificent bronze and marble statues were created of men with youthful, adolescent complexions and corded muscles, often depicted in scenes of physical struggle. Notable examples of this include “Laocoön and His Sons” by Agesander, Athenodoros, and Polydorus of Rhodes, and “Discobolus” by Myron.

Reportedly gay artists of the Renaissance, such as Leonardo DaVinci and Michelangelo Buonarroti, were taken with the unabashedly nude art of the ancient Greeks. It was during the lifetimes of these artists that the popular depictions of biblical figures began to more prominently evoke the ancient Greek ideals of male beauty. This fascination with nude figures put many of these artists in direct conflict with the religious authorities of the time, who viewed the prevalence of male genitalia in these commissioned pieces as salacious and sacrilegious.

Pictured above is Leonardo DaVinci’s “St. John the Baptist” in a classic example of this motif. Emerging from the darkness, St. John, in near androgynous form, gazes into the viewer’s eyes with unnerving eroticism. Though clothed, the pose that the saint holds is unquestionably sensual as his lips curve in a soft, yet mischievous smile as though he and the viewer share a secret. His left hand gently caresses his chest, near his heart very delicately like a lover would. In fact, this depiction of St. John is thought to be based on DaVinci’s alleged lover Gian Giacomo Caprotti da Oreno, more commonly known as “Salai.” Many speculate that the faces of many of DaVinci’s subjects in his paintings are based on Salai’s form.

Another famous artist that had tremendous influence on the depiction of religious figures in the Renaissance was Michelangelo, the genius behind the painted ceiling of the Sistine Chapel. To anyone that views the frescoes, the influence of the ancient Greeks will be immediately apparent; countless men in varying forms of undress crowd the walls, all of them possessing almost comically large muscles, their loins either completely nude or draped in dainty, flowing pieces of cloth. In the center of the fresco, framed by these men, is Jesus Christ himself. Depicted too with a hulkish physique and a cascading purple sash, the distinguishing Greek motif of the ideal male body can be seen in Jesus’ form as melding with the artist’s own personal tastes in men. The facial features of Jesus match closely with the descriptions of Michelangelo’s purported lover, Tommaso dei Cavalieri.

On the portion of the walls of the Sistine Chapel known as the “Last Judgement,” Michelangelo depicted 20 nude male figures, which he referred to as his “ignudi” (nude in Italian). In several places on the walls, several of these ignudi kiss each other in a display of homosexuality that was incredibly bold when one considers they were painted in the center religious authority in Renaissance Europe. Many religious figures of the day were appalled by Michelangelo’s blatant depictions of male bodies in a place of worship. Biagio da Cesena, a contemporary papal official, said of the piece “it was most disgraceful that in so sacred a place there should have been depicted all those nude figures, exposing themselves so shamefully, and that it was no work for a papal chapel but rather for the public baths and taverns.” So controversial were Michelangelo’s ignudi that loincloths were painted over them by papal decree a generation after the masterpiece was finished.

To this day, the influence of these artists can still be seen in the way that we, as a society, imagine the appearance of Jesus and other biblical figures. When Christian stories are told, in illustrations, television shows, and movies, they are still largely done so with attractive white characters, reminiscent of the homoerotic artistic pieces of the Renaissance.

The impact that these artists had on the portrayal of Jesus for centuries to come cannot be overstated. Michelangelo, Leonardo, and other Renaissance artists were instrumental in constructing the popular Western image of Jesus.

-

By Hannah Malia Kim

By Hannah Malia Kim

Phoenix: Spring 2009The thing I remember most about my girlhood in Beijing is the hutong neighborhoods. Especially, the way the houses were smushed together so that each shanty looked like a piece of a bigger thing. Almost like a brick and concrete accordion. I used to pretend that I could jump from one house to the next in giant strides, my shoes making thunks on the pavement, careful not to land in the places where the houses touched.

The homes were slanted, with corners worn and steps missing. If you tilted tour head a certain way, they looked like old kitchen wives with heavy bags on their shoulders. The people who lived in the houses like to squat low on the sidewalks, spitting into the street, cursing the weather and the war. The shingles of our own rood would come loose and fall away during thunderstorms, joining the rain in its descent to the earth.

Our shanty was really one half of a home that had been divided down the middle. Mother and I lived on one side and the Ming family lived on the other. Our house alone in the neighborhood still looked new with clean, solid walls of whitewashed concrete. The inside was dark and stank of car piss and garlic. The cat had claimed a section of the living room for himself, shitting and pissing neatly in the corner. I was afraid of it and stayed mostly in the kitchen, looking out the window at the people on their way to the market. My mother liked to watch them too, because they usually turned their heads back once or twice to glance at our house.

“See? They’re noticing our walls.”

My mother’s smile avoided her mouth altogether, leaving it hard and tight. I could tell she was smiling from a certain softening of the eyebrows.

“Our walls are cleaner and more expensive-looking.” I said.

“More Korean,” she said.

Once a week Mother put on some old clothes and scrubbed the walls. Afterwards, her hands would crack and peal from the harshness of the soap. The Mings never scrubbed their walls and our building ended up looking like it has been halfway dipped in bleach. On our trips to the market, Mother would stalk by the Mings’ front windows.

“Chinese women have no sense of cleanliness,” my mother would say.

I would nod, taking a second to work myself up for the next great stride.

The day I found the blue piece of glass was the same day the market vendors stopped obeying my father. It was also the day the light hit my mother in a strange way. It was early. Before the wives with small children could come out, but after the old women had already gone. The relatively empty street made me uncomfortable. Usually, I liked to run my fingers across the textured backs of lychee and Asian pears, hopping from fruit to fruit amongst a purposeful stream of women. Without customers, the vendors looked colorless and out of place. I stayed close to mother, keeping my eyes on the threads that hung up from her shirt sleeve.

“You’re not a toddler anymore.”

She quickened her pace, pushing me slightly until I was left perched between the dumplings and the vegetables. My father hung further back, the shiny buttons on his army uniform peeking through the opening of his jacket. He was standing stiffly, back arched and uncomfortable. The sun was rising at the mouth of the alley, but his figure blocked the light. I squatted where I was, folding my elbows together and resting my head on my hands. Ahead, I could see her approaching our usual vegetable stand. She picked up a few cucumbers and turned to leave.

“That’ll be 60 Yuan.”

“What?”

“60 Yuan. 20 Yuan each.” The vegetable vendor was a tall, skinny man with a pot belly that was puffing up and down like an Adam’s apple. His eyes skipped over to the mouth of the alley, tracing my father’s shadow. His hands were clutching and releasing strands of beans. “Sorry.”

I squinted to make out my mother’s expression, expecting to see the thin, firm line of her lips. But the outline of her body was slightly blurred, tinged with the gray-blue shades of early morning. The light shifted and I noticed my father had left the alley.

“I’m getting the cucumbers to make dinner tonight.”

The softness of her voice made my stomach hurt, and I reached down to scrape my palms against the city road. The rough texture of the pavement felt good. My fingers traced the outlines and ridges and grains of dirt: definite, concrete, and whole.

That’s when it happened. I felt a sharp pain in the bottom of my hand so that, for an awkward minute, I thought the road had bitten me. When I looked down I saw that a piece of glass had cut my palm. A flawless, clear blue piece of glass that was smudged on one corner with my blood. I looked around to see where the glass could have come from, but there was only pavement, and the vendor stands which had wood, cloth, and food but no glass.

My mother was coming quickly towards me, so I put the glass in my pocket. It seemed as good a place as any.

Mt father was an officer in the Japanese army. He stopped every Monday and Wednesday evening for dinner and sometimes on the weekends. He also stopped by for lunch occasionally and to go to the market. He usually came in uniform, the shininess of his buttons and shoes looking too sharp in the dimness of our home. On the evening after I found the blue glass, he arrived early. He sat cross-legged on the floor playing the dominoes with me. When the soup began to boil over on the stove, I ran across the room and stood on my tiptoes to stir it. The broth made sizzling sounds as it hit the burner. The cat was purring.

“Yong-hi, come here,” my father motioned me back to the floor. Mother remained seated in the kitchen, stroking the cat. She had been silent since his arrival.

I sat down. He looked different sitting on the floor. His legs made giant triangles, pulling his army pants taut and exposing his socks. He didn’t usually play games with me. I fingered the blue piece of glass in my pocked, careful to avoid the sharp edges.

“I found a beautiful piece of glass today.”

It took him a moment to focus on my words.

“Where?”

“At the market. I don’t know where it’s from.”

“Probably someone’s eyeglasses.”I looked at the eyeglasses sitting neatly on his face and tried to picture my piece of glass sitting there. It seemed to be too blue, but I wasn’t sure. I carefully fished it out of my pocket, watching my father. “Do you think it matches?”

He took the eyeglasses sitting neatly on his face and I tried to picture my piece of glass fitting there. It seemed to be too blue, but I wasn’t sure. I carefully fished it out of my pocket, watching my father. “Do you think it matches?”

He took the glass. In my father’s hands, it looked clearer than I had remembered, delivering only the faintest tinge of blue. There was even a slight bend to it, as if it had indeed been a part of an eyeglass lens. He studied it for a moment, turning it over in his hands. Then he looked at me, cupping his chin with his hand, thumb on one side and fingers on the other, in a way I hadn’t seen him do before or since.

“Do you think it matches?” I repeated.

He let his hand drop and shook his head.

“It’s just glass,” he handed it back to me, “is dinner ready yet?”

My mother stood up and dished the soup into bowls. She sometimes made Japanese dishes for the nights my Father ate with us, but tonight our kimchee-jiggae dinner was decidedly Korean. Halfway through the meal, she finally looked at my father, her lips thin.

“I’m sorry there’s no cucumber salad. There was trouble at the market.” My father’s face tightened and he shook his head in response. A few strands of hair, usually combed firmly to the side, fell across his face.

“How are we supposed to eat?” she said.

“I’ll bring you food from the base.”

I ate my kimchee-jiggae down to the very last grain of rice. I decided that I liked Korean food better than Japanese food even without cucumber salad.“The stupid vendor,” she said.

My father ate his rice slowly, careful to keep his mouth from getting too full. “You should have known. Too many men have already been sent home. I can’t guarantee you anything anymore.”

After dinner, my mother hovered in the living room, her hands drawn up, standing lightly on the balls of her feet. She resembled the cat, muscles taught, ready to spring. My father sat at the kitchen table, his glasses reflecting the light from the fireplace. The lenses looked like two small candles burning.

“Toshio, would you like to come back with me?” My mother gestured toward the bedroom she and I shared.

He took his glasses off and began cleaning them, making sure to get the corners near the nose piece thoroughly.

“No,” he said.

After my father left, I pretended to go to bed. By pretend, I mean I sat in the doorway to the bedroom, half-in and half-out, watching my mother stroke the cat.

The Ming sisters knew that my father was going to leave Chine even before I did, and told me so afterward. They were two years older than me and knew twice as much. Jia and Jie Ming were stringy, identical pole-bean girls whose upper teeth pushed past their lips, so that their mouths hung open in round O shapes. They liked to play outside after they came home from school, tempting me with dangerous yo-yo competitions or loud rounds of piaji- a Chinese version of Pogs.

I’d wait to join them until after my mother went to take her afternoon nap. She’s leave the cat to stand watch by the door, his flat cat-lips threatening to meow an alarm. To get past him, I put one or two anchovies in a small dish opposite side of the kitchen. Eventually, the salt smell would draw him away from his post. I could hear the wet sucking sounds of him eating as I slipped out the door.

“How was the market?” Jia Ming’s mouth stretched across her big teeth and into a smile.

“Did it smell like fish?” Jie said.

“It only smells like fish on Thursdays, dumb girl,” Jia said.

“If I’m dumb you’re dumb,” Jie said.

The sisters fell to the ground giggling, their mouths even rounder than usual. I stood to the side, admiring their synchronization. The glass in my pocket felt heavy, and I wondered what Jia and Jie would think of it. It if would change for them like it had changed for my father. And then I thought that whatever they thought of it, it’d probably be the same thing.

“Yong-hi,” Jia and Jie had finished laughing and were sitting up, looking at me. Their heads were tilted in opposite directions. I couldn’t tell if they had been whispering or not. “Let’s do something dangerous,” Jie said.

“Yes, somewhere far away,” Jia said.

“I can’t go far,” I said. The cat liked to sit at the window and watch me.

“Well we’ll go without you,” Jie said.

I considered showing them the glass again, just to get them to stay. But outside in their yard, standing in front of their dirty walls, I was afraid to take it out.

“Let’s try the abandoned house at the end of the street,” Jia said, “that’s not too far.”

I trailed behind them, purposefully stepping on the gaps between the houses and feeling a little thrilled at my audacity. I thought about mother and whether she was actually sleeping or just sitting quietly in her room, staring at her walls. Either way, I was sure the cat was with her.

When we arrived at the house I noticed that its walls, like ours, were made of concrete. But large sections of it were missing and broken. Glass littered the yard and the house on either side of the broken walls. There was so much glass that the ground looked like it was covered in clear, sharp snow. Dark, half-enclosed rooms were visible from the street, and I could even see a toilet, its lid gone, its bowl full of brown rain water. A broken bed frame, wood splintered and sticking up at odd angles, and some old children’s toys reminded me that a family had lived there. There was a yo-yo half-buried in the glass. I couldn’t imagine anything significant coming from here. Everything looked like only the outer shells of important things. I felt my hand slip into my pocket and wrap around my blue glass.

“What do you think of all this glass?” Jie said. She walked up to the house and began examining the scattered glass. She bent so low that the tips of her hair trailed across the broken edges.

I took a few steps backward, back toward the houses with people in them, “It’s awful,” Jia said. She took my hand, her fingers firm and filmy with dirt. It was odd to have one hand wrapped around the glass in my pocket and the other hand wrapped around someone else’s. My head cleared and I loosened my group on the glass, transferring some of the pressure onto Jia’s hand. I looked at her, but she wasn’t looking at me. We stayed and explored the house a little longer. On the way home, my hand was smudged with dirt from where Jia held it, and I was careful not to step in the places where the houses touched.

On Saturday my mother decided that it was time to visit the Buddhist temple on the outskirts of the city. She made her announcement while scrubbing the walls of our house. Her fingers, curled and wrinkled over rough cloth, were scrubbing the walls so hard I could see places where her skin was coming off. We packed a lunch and caught the 11:30 bus out of town later that day. I could see the cat in the window as we walked to the station.

The mountains surrounding the Buddhist temple acted like a high rood, enclosing the area. Even though it hadn’t rained in a few days, the ground, air, and wood felt damp and heavy with water. The roods of the temple building had jutted out into the small community, only to be sucked back into the leaves and branches of the mountains. It seemed as if the buildings were only partially available, likely to be consumed entirely by the mountains in the coming decades. I could hear the monks chanting in some private corner, their voices reaching much further here than they would in the city. I wondered what kinds of dwellings the monks lived in, and whether or not they were clean.

The doors of the main worship hall were open, leaving almost the whole side of the building exposed to the dampness of the mountain. But once we went inside, I was surprised to find the room warm and dry. My mother took off her shoes and walked quickly over to the table where hundreds of candles were burning like sprinkles of fire. She lit one and placed it at the corner of the table.

“What’s that for?” I asked.

“Your father,” she said.

Then she went to sit cross-legged in front of the Buddha statue, one pale bare foot facing up toward the ceiling and the other tucked beneath her. I sat behind her careful to imitate her position. We rarely came to the Buddhist temple and my mother never worshiped at home. Temple trips were reserved for the times when mother couldn’t scrub enough dirt off the walls, or when the cat was sick. I just watched her, tracing the graceful outline of her neck, and watching it disappear into the dark depths of her hair. Her lips were relaxed and pink, puffed out slightly. I liked to compare her to the giant golden Buddha, and their identical, erect postures made her look like a smaller, mirror image of the statue. I felt the outline and shape of the blue piece of glass in my pocket. It felt round and smooth, almost fragile, and I realized that the glass could have belonged to my mother. Or at least something she owned, like the glass handle of her yellow, blue and red fan from Korea.

I felt a sense of elation. In the unfamiliar softness of my mother’s mouth, the perfect brokenness of my piece of glass, I could feel the imprint of Jia’s hand in mine. I felt like the abandoned house must have felt before it fell apart. Like my father must have felt when he thought about Japan. It was a scattered feeling-not altogether wholeness, but something like it.

“What’s that?”

I was so surprised to hear my mother break the silence that I didn’t answer her right away.

“A piece of glass I found at the market.”

She stood up in one smooth motion. “Throw it away,” she said, her lips thin,

“You can’t carry around a piece of garbage in your pocket.”

I waited until she was occupied with her shoes before hurrying over to the candle table. I stood the glass up on its side behind my father’s candle. By candlelight the glass looked so blue and thick that it seemed to curve around it, acting as a sort of enclosure. The glass was close to the flame, and I thought the flame might melt a groove in the glass.

That night, my pocket felt empty without the glass, and I cried quietly, hiding my face underneath the blanket. But I fell asleep quickly, and in the morning, it took me a minute to remember why I had been sad the night before.

My father left us the following week. He kissed my mother goodbye and gave me a nod while he put on his shoes. I did not expect to go with him. He was going home.

On the evening after he left, my mother sat in a chair, staring at the wall. I liked to think that she was imagining the giant Buddha statue in front of her. I remember noticing how scarred and broken her hands looked. There were raw spots and cuts where the skin hadn’t healed from the last time she scrubbed the walls.

-

Written by Sadie Kimbrough

Written by Sadie Kimbrough

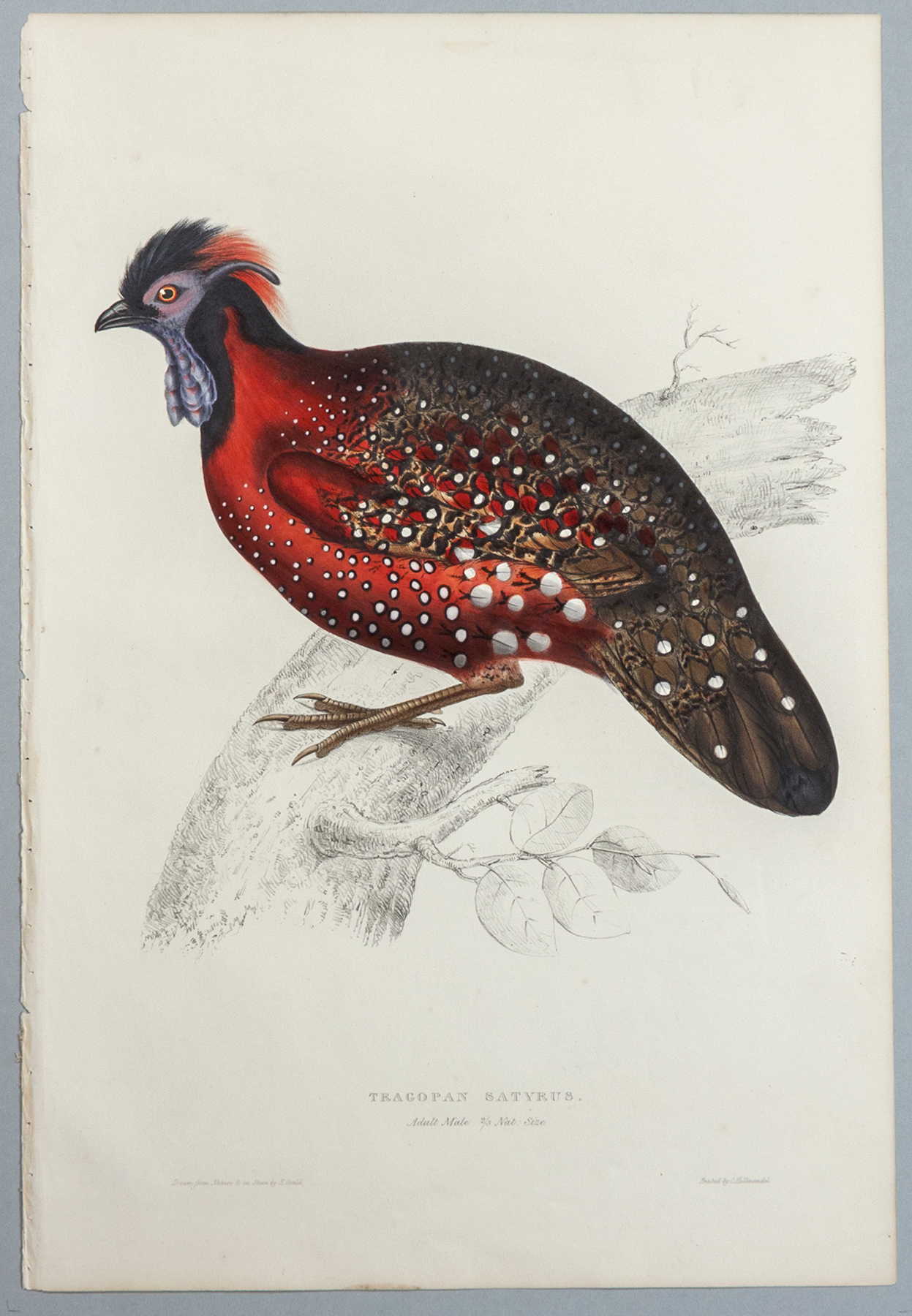

Edited by Lynda Sleeter“Put a bird on it,” chant the characters in the sketch show Portlandia, mocking the trendiness of bird-themed decor in modern boutiques and Etsy shops. The skit pokes fun at the cultural phenomenon of birds in the art world.

The flying creature is an all too familiar motif in art and media. Birds may symbolize freedom and transcendence in an oil painting or psychological torture in a Hitchcock film. Even Phoenix is named for one of the most common avian tropes in literature.

In Tennessee, we see birds everywhere, whether they be rambunctious geese along the river or simple backyard cardinals. If you’re looking for artistic inspiration, it’s not difficult to be charmed by the prevalence of feathers and beaks.

The current exhibition at the McClung Museum of Natural History & Culture exemplifies this ubiquity. “Between the Hand and Sky” features the work of British illustrator Elizabeth Gould and provides insight on how “bird art” initially took flight 200 years ago.

In the early 19th century, Gould set the stage for ornithological illustration. Best known for her hand painted lithographic prints of taxidermied birds, she possessed mastery in a field she lacked invitation to as a woman.

When Gould’s husband, a well-known taxidermist, planned to publish over 100 hand-colored lithographs of his birds, she asked who would assume those artistic responsibilities. John replied, “Why you, of course.”

Despite Gould’s extensive handiwork, her husband discredited her work and for many years, she remained inadequately represented in the world of scientific illustration. The pieces on display at McClung showcase the elegance and sophistication of Elizabeth Gould’s work, not as an assistant or wife, but finally, as an artist in her own right.

Nearly 200 years after the publication of Gould’s work, bird art maintains its relevance, not just in science but in both ornament and function.

The birdhouse has existed in Western culture for centuries, whether it takes the form of a man made tree cavity or an elaborate cage. This summer, Knoxville artists extended this tradition to raise money for the UT Gardens, our official state botanical garden.

The 2021 Art in the Gardens Project features dozens of birdhouses decorated by local artists: young and old, amateur and professional. “Home Sweet Home: A Birdhouse Exhibit” draws attention not only to the creative achievements of the artists, but to the vibrancy and verdancy of the gardens themselves.

The centerpiece of Gwendy Kerney’s “Birdhouse of the Rising Sun” is a one-eyed sun goddess made of metal and decorated with acrylic paint. The bright hues of orange, red, and blue mesh beautifully with the surrounding green trees. Kerney accurately describes her piece as “joyful fun.”

Near the central gazebo sits one of the most intricate birdhouses in the gardens. James M. Cantu’s piece, “an experiment in dot painting,” represents the Smoky Mountains, featuring a speckled blue river descending layers of mountainous terrain.

Some artists take a more offbeat approach, like Michael B.R. Smith’s brainchild “Space Bird,” which depicts a birdhouse “experiencing an atmospheric entry process.” The metal assembly includes 210 feet of 9 gauge steel wire, despite only measuring about 3 feet in length.

The birdhouses will be sold through an online auction with all proceeds benefiting the UT Gardens. Bidding starts on Monday, September 13 and ends on Wednesday, September 22. The “Home Sweet Home” exhibit is available to the public until the end of the auction.

Although the Portlandia sketch is rich in sarcasm, birds absolutely continue to intrigue us in our books and backyards. Perhaps you can’t just slap a canary on a canvas and call it art, but current Knoxville exhibitions prove that with intention and whimsicality, you can definitely put a bird on it.

Photography by Sadie Kimbrough