By Clint Liles

By Clint LilesEdited by Ben Hurst

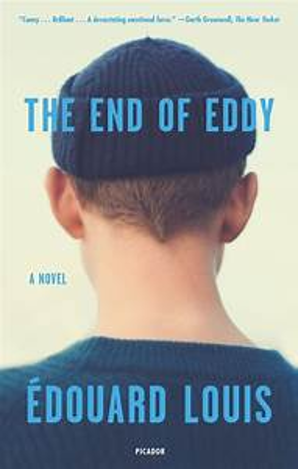

When I first read The End of Eddy all I could find was its problems, yet one year later the message of the book still resonates with me. French author and commentator, Edouard Louis shares how he comes to terms with his sexuality in an impoverished village in Northern France. He opens with the observation that “from my childhood I have no happy memories,” which may seem bleak, but he qualifies this statement by adding, “I don’t mean to say that I never, in all those years, felt happiness or joy. But suffering is all consuming: it somehow gets rid of anything that doesn’t fit into the system.” Although Louis writes on his experience in a country halfway across the world, many young individuals within the LGBTQIA+ community, myself included, will understand his story as their own: making it an unforgettable and personal read.

From the beginning, the book spoke to me because I grew up in a small town in rural Appalachia, and I identified with the author’s struggles. Louis, who is called Eddy, as a young boy is considered an effeminate and odd boy throughout grade school which results in him getting bullied from an early age. His father, who dropped out of school to work at the local factory, insists on him to take up soccer to “toughen him up,” however it results in more bullying for his lack of understanding and skill in the sport. The town I lived in was a blue-collar community where the majority of the population worked in factories. My connection with young Eddy was heightened because my dad was a football coach and like Louis, I did not have much concern for the sport and much preferred reading or shopping with my mom. Eddy connected with me from the beginning, bringing to mind my small hometown and the struggles I faced with coming to terms with my sexuality.

Louis notes that he comes from a family of violence, that his grandfather beat his grandmother and that his father has uncontrollable anger issues as well. He continues to note how this cycle is continued as his sister marries early to a young man who struggles with anger issues as well. Louis states that this violence is not uncommon in his village as several other families struggle with the same thing and as a result several children around him grow to be violent as well. Louis relays that this correlates with an issue of alcoholism in the village, speaking of the many times his brothers and father would be at the bar getting drunk. An article recently published by the University of Michigan notes that alcohol is the most widely used substance abuse in Appalachia, surpassing dug abuse. Alcohol abuse has long been a problem here correlating with the poverty in the region. Just like how Eddy’s family struggles to live their day to day lives, thousands of Appalachian families face the same thing.

Louis does not spare details of the poverty of his family: stating they lived in a small home that leaked often and oozed with dust in the spring coming in from the rural fields. Eddy had severe asthma, yet his parents preferred that he lied about it because they could not afford the medications to control it. While his family faced an incredible amount of poverty, he notes that they were still proud since they did not rely on government assistance. Coming from a small town in rural Appalachia, it seemed that the people who needed the assistance the most refused it the harshest. In this moment it felt as though Eddy’s family was a part of Appalachia as well, refusing assistance and seeking to work things out themselves.

Louis notes later in the book that he and his male cousins watched pornography while their parents were not at home. Eventually, this progressed to them experimenting with homosexuality until Eddy’s mother discovered them in the woodshed. Eddy notes that his mother did not say anything but instead quietly walked away. Eddy’s cousins quickly turn the story and said that it was Eddy who started the idea which resulted in more severe bullying by his peers. To solve this issue, Eddy decided he needed to appear more masculine and began dating a couple girls. I remember when I was growing up and feeling the need to fit in with others to survive my small high school. The constant fear of someone figuring out that I was gay lingered with me everywhere I went. Eddy’s futile attempt to date women is a common occurrence to every young gay kid coming to terms with their sexuality. Just like for Eddy, this is a moment I knew that I was gay and had to give up on the visage I worked so hard to put on for my community.

Overall, Louis writes a piece that will resonate most deeply with young LGBTQIA+ individuals who struggled or are struggling to come to terms with their sexuality, but his story is also a story that all Appalachian readers will recognize and appreciate. For me, the memoir felt personal and intimate as Louis revealed areas of his life that many, myself included, would prefer to cut out and hide from others. The End of Eddy is certainly not an easy read, but it is worth it for readers willing to take the time to consider the larger forces shaping life both here in Appalachia as well as in France.